Rewind time in real-time

The main feature of my Project: Merge old game prototype is its time rewind mechanic. It allowed the player to rewind the state of the game in real-time, up to any moment. The end-goal was to allow the player to use this ability to solve different situations, such as combats and puzzles.

Here’s a quick demo:

So when I saw a very similar mechanic in the latest Legend of Zelda game, I was quite intrigued:

As such, I plan on detailing my own implementation and then compare it to what we see in that game. While it isn’t unlikely that the devs at Nintendo went in a completely different direction, I believe it might still be interesting to see what problematics they might have encountered and how they solved them.

Defining the problem and the specs

The first step here is to define the specifications of what we want this mechanic to achieve: what to rewind? rewind to when?…

There are two types of things we want to be able to rewind for now : the rigid body objects (like

the cubes lying around the scene) and the player.

The rigid body objects should be able to be rewinded along their physical state: position, velocity,

rotation and angular velocity.

The player should have is position and camera rotation rewinded.

We might also want to rewind other things at some point, like the gun and bullet animations, player interactions (like pulling a lever), particle effects,… As such, we need to design a system that can handle those type of entities, which will most likely have some custom behaviour.

Also, we will not try to compartmentize which objects should be rewinded for now, we will assume that we’ll rewind everything. However, it is not necessary for the rewinding itself so this is a problem that can be tackled separately.

Implementing the rewinding

Now that we have an idea of what we want, let’s jump into the heart of the subject. For simplicity’s sake, we will exclusively focus on the rewinding of rigid bodies. The other objects to rewind will follow a very similar pattern after all.

The first thing to note is that we’re dealing we’re not dealing with a purely procedural physical state, in the sense that we don’t have an easy way to retrieve its value at any particular time. In fact, we are using physics simulation withe discrete steps. Some punctual forces can be applied to the object and even if we keep tracking them all, this is not going to be easy to back-track the simulation along them.

As such, the first solution that comes to mind is to save the physical state itself as time advances as discrete events.

struct FTrackedPhysicsState

{

FVector PositionW;

FVector VelocityW;

// Here we'll use Euler angles, but quaternions are likely to be a better solution down the line

FVector RotationW;

FVector AngularVelocityW;

double Timestamp;

};

This is not the most precise way to register and replay the state, but it should allow us to approximate it using interpolation.

A first approach would be the following:

FVector FTrackedPhysicsState::InterpolatePosition(

const FTrackedPhysicsState& PreviousState,

double Time,

double LerpFactor)

{

return FMath::Lerp(PreviousState.PositionW, PositionW, LerpFactor);

}

FVector FTrackedPhysicsState::InterpolateVelocity(

const FTrackedPhysicsState& PreviousState,

double Time,

double LerpFactor)

{

return FMath::Lerp(PreviousState.VelocityW, VelocityW, LerpFactor);

}

FVector FTrackedPhysicsState::InterpolateRotation(

const FTrackedPhysicsState& PreviousState,

double Time,

double LerpFactor)

{

// Convert back to Quat to use Slerp, then back again to Euler.

return FQuat::Slerp(

FQuat::MakeFromEuler(PreviousState.RotationW),

FQuat::MakeFromEuler(RotationW),

LerpFactor

).Euler();

}

FVector FTrackedPhysicsState::InterpolateAngularVelocity(

const FTrackedPhysicsState& PreviousState,

double Time,

double LerpFactor)

{

return FMath::Lerp(PreviousState.AngularVelocityW, AngularVelocityW, LerpFactor);

}

FTrackedPhysicsState FTrackedPhysicsState::Interpolate(

const FTrackedPhysicsState& PreviousState,

double Time)

{

check(Time <= Timestamp && Time >= PreviousState.Timestamp);

const auto LerpFactor = (PreviousState.Timestamp == Timestamp)

? 1.0

: (Timestamp - Time) / (Timestamp - PreviousState.Timestamp);

FTrackedPhysicsState Result {

InterpolatePosition(PreviousState, Time, LerpFactor),

InterpolateVelocity(PreviousState, Time, LerpFactor),

InterpolateRotation(PreviousState, Time, LerpFactor),

InterpolateAngleVelocity(PreviousState, Time, LerpFactor),

Time

};

}

The interpolation result clearly won’t be the best, especially for the position. There is likely going to be visible artifacts. However, this is something that can be easily iterated over with better interpolation for each member.

Now that we now how to track the physics state and to interpolate between them, we have what we need to do time rewind. We just need to store these states regularly in a container.

However, we start to reach a problem: when do we save these states. If we save them every frame and never free them, with enough rigid bodies in our scene we’ll overload our system memory.

A first approach would be to set a hard limit to how many states can be saved per body, this way we can keep the memory footprint predictable. But it limits how many states we can save.

A second cheap iteration is to only save the states where the object is moving around. There is no need to save consecutive states of the object not moving. This should help in most situations, but it also has its limit. Some situations cannot profit from this. An example would be a cube endlessly spinning in zero gravity.

A third iteration then would be to reduce the overall amount of state saving, by only saving the state when it is relevant, and let the interpolation do the heavy lifting.

For this third iteration, what I did was that I went ahead and compared the current velocity and angular velocity with the ones from the latest saved state. If they differ too much, the current state is saved.

To be more specific I check if the change in direction and relative norm goes beyond a certain threshold for each one.

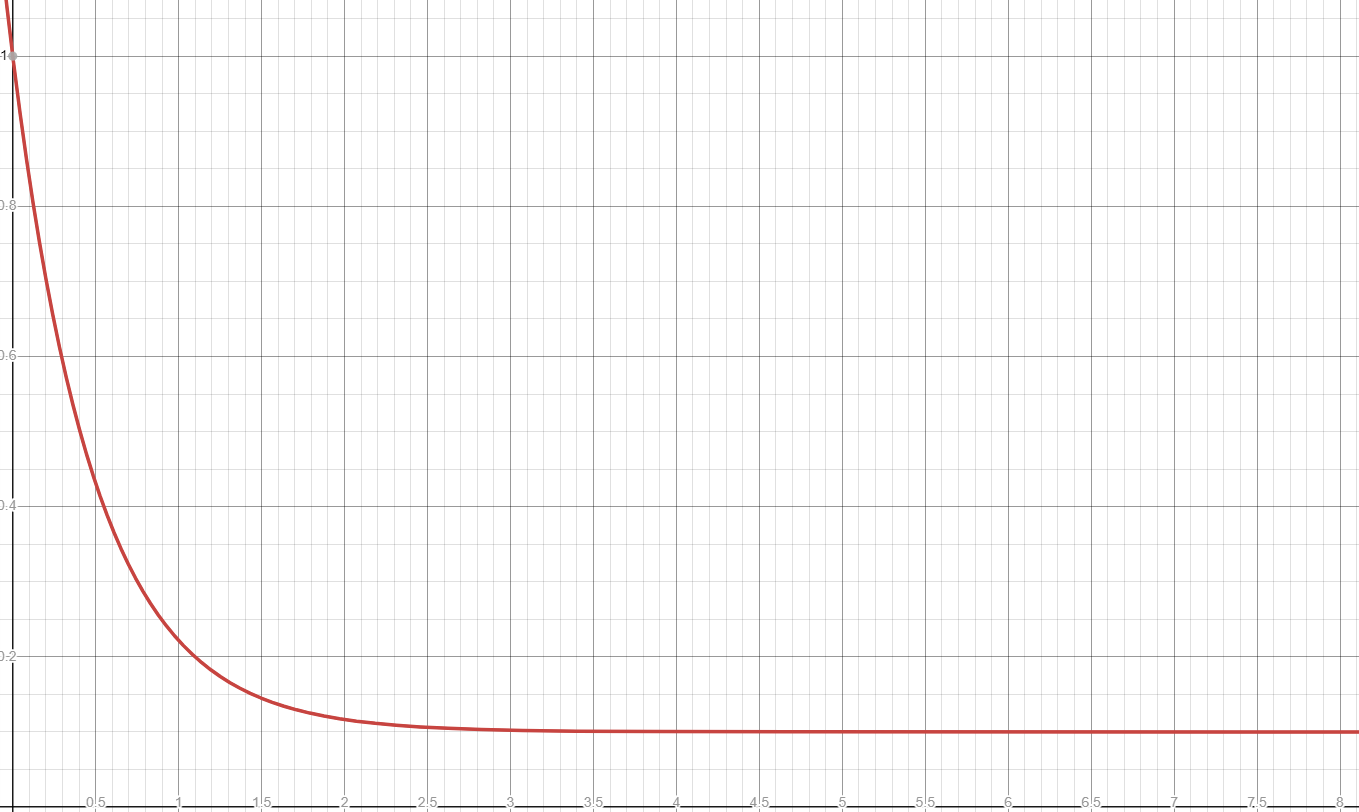

As for the threshold itself, I actually use a varying threshold based on an exponential falloff based on the time

passed since the last state save:

This allows the system to save slight changes over longer periods of time while avoiding over-saving when you have a very quick succession of changes.

This however brings its own set of issues as now more than ever you need to experiment yourself to find the most appropriate parameters, which are not obvious and will require a lot of iteration depending on your situation.

How does the Zelda version compare ?

Let’s just roll it again here:

If we go back to the Rewind power from Tears of the Kingdom, we can see that they seem to have a very similar situation. There are a few differences though:

- they only rewind one object, and lets it interact with the rest of the world (which is still going forward in time) as an unstoppable force of chaos. The prototype was trying to rewind the entire scene, which is a lot harder to do. There approach works way better for what they want to achieve, since it is simpler.

- The object does not keep its momentum when the rewind stops. This is simply a matter of resetting the momentum to zero once we stop rewinding.

- They allow the player to rewind the object up to a certain duration back in time. The prototype does not.

- They cut the periods of time when the object has no momentum or is not interacted with (notably by using the Ultrahand power)

Overall it is still very compatible with the approach I took, as long as you do some alterations.

With their setup, they could simply save the physics state at certain time intervals and dump the states which go beyond their imposed time limit, limiting the memory impact. Using streaming and taking a look at how the actual game works, I expect them to only have to track a few hundreds of bodies at once at most, which is very manageable.

I would go as far as to suggest that they actually did not even save the velocity and angular velocity in the physics state, since they don’t need to reapply the momentum when stopping the rewind.

This would have allowed them to bypass many issues that I encountered myself in a very elegant way.

Some suggestions for improvement

Better interpolation

We should be able to improve the position interpolation easily by integrating the position with its velocity. You might be tempted to simply use one of the two states, but you’d end up with two issues: there will likely be a big mismatch between this computed position at the end of the segment and the actual position of the other state, resulting in a non-continuous trajectory when swapping segment. Also since we’d only be using velocity, we’d keep straight interpolated trajectories. You must also decide which state to use as a start point.

The trick to this is actually to compute this value from both state and interpolate between the results. This way the interpolated trajectory will remain continuous, and the trajectory will be parabolic: https://www.desmos.com/calculator/uc2f9a1ybt

FVector FTrackedPhysicsState::InterpolatePosition(

const FTrackedPhysicsState& PreviousState,

double Time,

double LerpFactor)

{

// Do a linear interpolation between a forward and a backward trajectory.

// Results in a parabolic trajectory: https://www.desmos.com/calculator/uc2f9a1ybt

const auto PositionWFromPrevious = PreviousState.PositionW + (Time - PreviousState.Timestamp) * PreviousState.VelocityW;

const auto PositionWFromCurrent = PositionW + (Time - Timestamp) * VelocityW;

return FMath::Lerp(PositionWFromPrevious, PositionWFromCurrent, LerpFactor);

}

You can use a similar approach with rotation.

Interpolation could be improved further still using splines, but I’ll leave that to the reader for exploring.